Reading time: 12 minutes

Soon after I learned the rules of chess, I started playing a lot of games against myself. To be clear, this was not because I was a shy and introverted child who was generally happiest sitting in a quiet room with a chess set, some books about dragons, and no friends. Or, not only that.

I simply wanted to get better at playing, and it seemed to me like handling both white and black at the same time was a good way to go about it. It never really worked, though. Every time I tried a tactic, my opponent (being me) knew what I was planning, which I (being me) knew they would anticipate, and so on and so forth. I’d wind myself up in circles and never really get anywhere.

I think about that sometimes when I’m coaching other writers at M+R. I often tell folks that making a practice of self-editing is a great way to level up: finish your draft (email appeal, social media post, video script, or whatever else), walk away from it for a minute, and then go back and make changes as an editor would. And I do think it can be a very productive process, but I also know how easily it turns into playing chess against yourself.

How can I give myself useful writing feedback? If I knew how to do a better job, I would have drafted it that way to begin with!

The problem lies in thinking of editing as a process of correction — where a better, more knowledgeable, or more experienced writer fixes the shortcomings in a draft. That’s not how we should approach editing. Instead editing is, or should be, a collaboration — where multiple perspectives combine to shape content so that it can better connect with audiences.

If you are self-editing by asking “how can I make this writing better?” you will probably have a difficult time. You may even be tempted to ask an AI to do it for you — and while that might cover some basics, an algorithm literally does not have a perspective and is not likely to give feedback that will help you become a more inspirational writer. What works best is to ask yourself specific questions that help you see your own writing through fresh eyes and spot opportunities for revision that will make your copy sing.

Q: Do I know what my goals and guidelines are?

Okay, so really you should have asked this before you started drafting at all. One of the leading causes of lukewarm, deflated, meandering copy is a lack of clear purpose. Before anything else, make sure you understand who your audience is, and what the goal of your message is — whether that is revenue, petition signatures, clicks, education, or anything else. You can’t make your copy more effective or engaging if you don’t have a clear sense of your purpose.

That pre-writing stage is also where you should be considering the ethical contours of your creative. What tropes or story elements might reinforce harmful stereotypes or otherwise be problematic? Whose voices are you choosing to elevate? What brand guidelines do you need to follow to be transparent and honest with your audiences?

We’ll come back to editing for effective and ethical creative, but ideally these are choices that are clear before you ever type a word.

Q: Does this copy start in the right place?

Your lede (the first few lines, usually up to the first call to action) is the most important part of your message. It’s where you set the emotional tone, establish the context of time and place, and let the audience know that this content is for them. If you lose a reader here, they’re gone.

But writing an irresistible lede is hard, and sometimes the very first thing you write isn’t the most powerful thing for your audience to read first. When you are self-editing, take a look at your first two paragraphs. Is this truly a compelling starting point? Or do these opening lines just reflect your own process of writing your way to the thing you really wanted to say?

Tear down that scaffolding and you will often find that three or four paragraphs in, you arrived at the emotional core. Or you dropped in a quote that really hits home. Or you managed to work your way past the who/what/where/when context-setting, and really capture the moment at hand.

That’s your lede — move it up to the top. The rest, the scaffolding, you can delete, repurpose, or simply drop below the fold to help add nuance to your case for giving or theory of change.

For more thoughts on ledes, check out this blog post with 22 Email Ledes that Always Work!! Keep these in mind next time you are self-editing, and you may find your ideal lede lurking a few lines in to your draft.

Q: What if this was the first message I ever saw on this topic?

Remember: you are not normal. You are a person whose job is to carry passion and in-depth knowledge about your particular cause or organization. You probably spend a lot of time thinking about your issue space, and closely following the news, and Being Online.

Fair enough. Me too!

Your audience, on the other hand, is mostly full of normal people. People who care, yes, or they wouldn’t be your audience — but who very likely have other things on their mind. They might not get breaking news alerts on their phone. They probably did not read your last email, and if they did they do not remember it. They do not keep a carefully curated and constantly shifting mental list of which United States Senator is actually the worst. (Ted Cruz, then Josh Hawley, or the other way around? Wild card: what about Tuberville?)

One way to edit your own content is to imagine that you have no previous knowledge of your topic. If you are addressing breaking news, a piece of legislation, a court case, a research finding, make sure you give enough background so it make sense to someone who has not heard of it before. Eliminate, or clarify, any jargon or Official Language that may be opaque to readers.

This doesn’t mean you need to turn your copy into a Wikipedia article. Most of the time, you don’t need a policy briefing in order to make sense of the call to action. But make sure you are explaining acronyms and providing background information, even if that explanatory content needs to go below the fold.

Q: What if I cut out all the plain text?

The greatest enemy of a direct response email is the spam filter. The second greatest enemy is time.

Much of your audience isn’t reading what you write — they are scanning, skipping down the screen looking for key phrases that are relevant to them. And they are only spending about 10 seconds doing that. Your job is to make that process easy and effective.

Use formatting — bold, bullets, text color, highlighting, graphics — to draw attention to the most important pieces and make the message scannable. Now, delete everything that is still plain text. If you read only the bits that have special formatting, does your message still make sense? Is the call to action clear? If not, look for ways to use visual cues to draw attention to the most important content.

Q: How does it sound? How does it look?

It’s easy to follow your own train of thought. The story you are telling, the argument you are making, the phrasing you have chosen all make perfect sense. To you. Someone else who does not live in your head might get lost. In order to identify those confusing passages, or spot clunky or inelegant writing, it helps to focus on the physicality of the words on the screen.

The simplest solution for most people is to read your copy out loud. Some of it will be confusing, hard to follow, bland, or repetitive. You might skip right past those spots when giving a quick, silent re-read, but they’ll stand out when you trip over them aloud.

For Deaf people, or those who are strongly inclined to visual learning, you can achieve the same results with careful attention and a focus on the way the content looks on screen. Read through your text, slowly, lingering on each line and paying close attention to the shape of your text.

For example, you should prefer short sentences and simple syntax. If a sentence, when spoken aloud, seems to run on and on — with too many commas, and subclauses, and ideas stuffed into it — that will be apparent to someone who reads aloud and listens closely, and it will also be apparent to someone who has an eye out for all those fussy elements and knows to simplify in order to help the reader and keep things punchy.

Read that last sentence again, either aloud or with a close eye. Doesn’t it cry out to be broken up?

Some other things to listen for or look for:

- Repetitive language. Did you call the same bill “outrageous” in two consecutive paragraphs? Time to take a trip to good ol’ thesaurus dot com.

- Repetitive structure. This happens a lot, but you can fix it. It might not be apparent at first, but it stands out when read aloud. Some of us have a tendency to say “this, but that” a lot while drafting, but you can clean those up in a self-edit.

- Long paragraphs. Do you need to pause for breath in the midst of a paragraph while reading aloud? Will that paragraph fill up an entire mobile screen? Break it up, or use bold or other formatting to guide the reader.

- Wonky language and jargon. Does this sound or look like a policy briefing? Can you imagine one human being saying these words to another human being? In real life?

- Just plain awkwardness. If you’re on the fence about whether a bit of copy is working, then it is not. Remember, your copy will almost always work better in your head than in your audience’s. When in doubt, change it — or flag it in a comment to ask an outside editor for a gutcheck.

Q: Does my copy include all five elements of effective creative?

By this point in this post, it is probably apparent to you that we have a LOT to say about direct response copy writing. In fact, M+R has published an entire Guide to Effective and Ethical Direct Response Creative. Go read it!

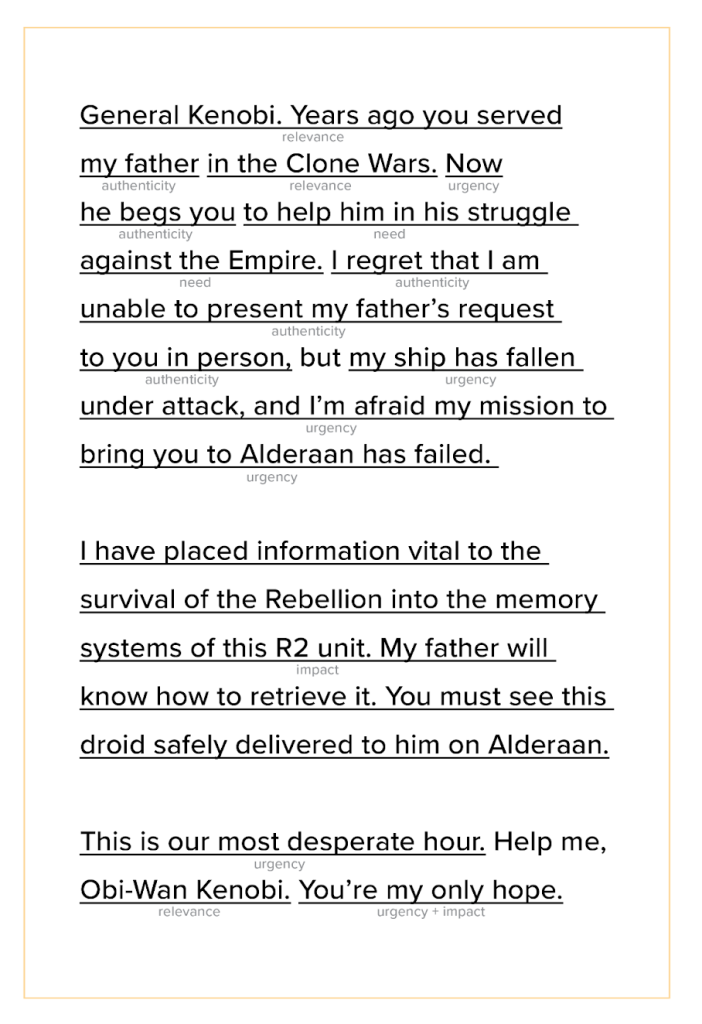

I won’t rehash the whole thing here, but one helpful tip is to review your lede, or your full copy, and highlight the places where the elements of effective creative show up.

Very briefly, those elements are:

- Need: Who needs help? What needs to be changed? What problem needs solving?

- Impact: How will the audience affect the situation or contribute to change?

- Urgency: Why is right now the moment to take action?

- Relevance: Why should the audience care?

- Authenticity: Why is the speaker someone who the audience should listen to?

Here’s an example from an ancient text, highlighting where those elements show up.

Take a similar lens to your lede, and identify where the elements of effective creative are showing up (or not). This can be an especially useful exercise when you have a vague sense that your copy isn’t compelling, but can’t quite put your finger on what is missing. Very likely, you are missing urgency, or a clear statement of impact, or some other element.

Q: Does my copy align with my organization’s, community’s, or own values?

With tight timelines and heavy workloads, it’s not unusual to narrow our focus to the mechanics of writing. Is the case for giving clear? Did we explain the match accurately? All very important, but a good self-editor will also be mindful of how copy is expressing values — or failing to live up to them.

Once again, you’ll find more depth on this topic in the M+R Guide to Effective and Ethical Direct Response Creative. For now, I want you to think about the stories you are telling.

Keep an eye out for places where your narrative may be sensationalistic, or exploit suffering to trigger a response. Make sure the agency and dignity of the individuals or communities you serve shines through, and that you are not portraying them as passive recipients of aid or a problem to be solved. Ask yourself how the subject of the story you are telling would feel if they read your copy. Be conscious of power dynamics and careful not to drift into white saviorism or other problematic tropes.

As we noted at the outset, you should be clear on your core values before drafting begins. Hopefully, your organization has clear brand guidelines that help to shape the ethical viewpoint of your content. But remember that you are also bringing your own conscience to this work — a self-editing step is a place to watch out for your unconscious biases and make sure you produce content you can be proud of.

In the end, that’s what editing your own writing is about. You may not be able to teach yourself to be a better writer, any more than 8-year-old me could outwit himself with a queen sacrifice. Instead, review your copy from a specific, intentional perspective that allows you to experience it anew.

And then hand it off to someone else to keep that collaboration going.

————

Will Valverde is a senior creative director at M+R and co-writer of The M+R Guide to Effective and Ethical Direct Response Creative. Over the past 18 years, Will has written millions of words of fundraising, advocacy, and marketing copy for nonprofits of all types. He also leads regular writing and editing trainings for M+R staff and clients.