Data as Decision in Grantmaking

In grantmaking, one word makes more eyes glaze over than any other – data. Those who find it fun are called nerds. And for everyone else, it can bring up feelings of boredom, overwhelm, and confusion. In philanthropy, there can also be worries of time commitment, grantee burden, complicated methods and, frankly, resources circling the drain without adding any function or value.

With one shift in our understanding about data, we can reclaim a sense of wonder, creative agency, and value in our data work: Recognizing that information does not equal data and data does not equal knowledge.

The key force in the formula is that data is actually a decision. More specifically, datamaking is an action whereby we transform information into data so that data can contribute to knowledge.

Information is everything that is coming at us. It is all around us whether we seek it out or not. However, to have data requires intention. We make information into data when we explicitly attach it to a question and explicitly or implicitly connect it to an approach for making sense of it. Building knowledge is a social process where we make meaning together. We utilize datamaking as part of shared meaning making.

To learn more about knowledge work and its role in grantmaking, check out the post Beyond the Newest Philanthropy Buzzword: Knowledge Work is Core to Equitable Change.

The Creative Power of Datamaking

Focusing on the action of datamaking opens a world of possibilities for developing knowledge.

Data is part of the tracking and monitoring innate to grantmaking and can be part of intentional organizational learning processes. However, datamaking has added power because it can beused to deepen strategic social processes of foundation-funded change.

Datamaking can ground processes of joint learning that energize grantee relationships. It can contribute to exchanges and interactions that are at the heart of nonprofit network building. Datamaking can enhance capacity building efforts through group questioning and analysis. It can support funder and cross-sector collaborations and the processes of decision-making. Datamaking, as an aspect of knowledge building, can even contribute to civic engagement and participatory democracy.

Keys to Datamaking Success

Many of the tools and techniques that we have learned about data design and collection continue to be relevant in datamaking, such as:

- Ask clear questions and prioritize which data points, or combinations of data points, are most relevant to answering the questions.

- Determine the best type of question, like multiple choice, Likert scale, open or closed ended, short text, or long text.

- Ensure consistent processes for collecting the most accurate data.

- Be internally and publicly transparent about the processes for data collection.

In addition to these traditional elements of data collection, datamaking requires an additional three elements.

Deciphering Key Questions

It is equally as important to determine what to collect as it is to identify what we can stop giving our attention. When we ask our colleagues, board, and partners what questions they have, there are often quite a few. However, when we initiate a more practical conversation, we can determine which questions will be most useful.

In working with a nonprofit intermediary, we brought together a knowledge team that met monthly over the course of nine months. The team included the director, board chair, administrative marketing and communication staff and a community engagement consultant. I wanted to move beyond what was interesting information toward understanding what would be most important to know. Each member of the team brought a different perspective based partly on their work in the organization.

I asked each person to fill in cells in a matrix. The matrix prompted folks to identify what they wanted to understand better, what and how they already collected data in their day-to-day work, and what statements they really wanted to be able to make with evidence. It is important to prompt thinking about this last one because there are many things we can say about our work that don’t require us to invest time and resources into long term data collection.

Learn more about how thoughtful and well-constructed questions are crucial to knowledge work and data making with the post Grantmaker’s Questions as a Way Toward Change.

Identifying What Matters Most to the Work

Data collection as it occurs in the nonprofit and philanthropic sector traditionally aligns with a linear equation of vision to mission to goals to outcomes with data brought in at the end stage of determining if outcomes have been achieved.

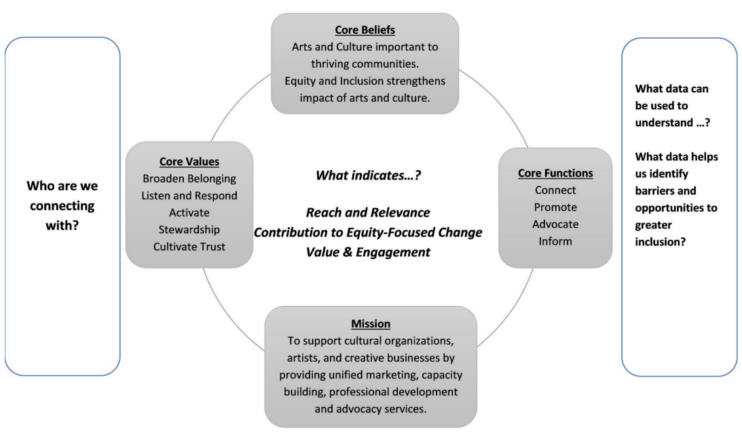

Datamaking invites a more holistic framing whereby “what matters most to doing the work” is centered within the four directions of core mission, core beliefs, core values, and core functions. In addition, the framing includes two bookends to these core items, which are who are we connecting with and what data can be used to best understand. When equity is prioritized, the question of data is extended to include what data can help us to notice barriers and opportunities of greater access and inclusion.

The following image conveys what this looked like in practice for the same cultural intermediary that used the matrix tool above.

Visualizing Where Meaning Making Can Happen

“Mapping” activities are often the starting point of identifying data collection opportunities. We are taught to create an organizational chart or a program activity graphic or a network diagram of organizations needed to address an issue like homelessness or educational equity. We use these visuals to point to existing data sets and who controls access to the data.

For datamaking, visuals like charts, diagrams, or maps are important for more than data collection. These visual analysis tools illuminate potential connections and spaces where relationships exist or are possible. These are opportunities for meaning making.

Imagine a diagram or organizational map that you have created or used for data collection purposes. Now add a layer in your mind showing the people represented in those circles and lines. These spaces offer opportunities for, not just collecting data, but explicitly and intentionally bringing data into conversations in ways where folks can come to deeper understandings of each other and of what is possible.

Most importantly, in this current phase of philanthropy and understandings of social change, we are acknowledging that shared meaning making, and datamaking as one aspect, are central to the work of change itself.

Equity Throughout

One of the main reasons for embracing datamaking is that it allows us to more clearly notice the places where equitable practices can be strengthened. These are the opportunities for asking: Who is involved in determining the questions? Who gets to say what information is important enough to become data? Whose perspectives or frameworks are valued in interpreting data?

In considering equity in datamaking, it is important to first shine light on misconceptions or assumptions about data. Here are three myths about data specifically related to equity.

1. Decentralizing Data

The notion of decentralizing data has become popular in philanthropy. However, grants to create publicly available data sets or data training for marginalized groups or under resourced organizations do not by themselves lead to equitable outcomes. While exposure to data itself is one step, access is a more complicated notion that involves the ability to engage with the data and use it in ways that improve life outcomes in communities.

2. Policy Change

Furthermore, the implicit idea that widespread quality data leads directly to positive policy change is also not accurate. Although data can be used in advocacy and policy change processes, even the most rigorous data cannot achieve policy change without shifts in our understandings and the self and collective narratives around pressing issues.

3. Storytelling

Storytelling has also become a prominent concept connected to data processes in philanthropy. The underlying assumption has been that collecting stories as data or even using data to tell stories will inherently bring a more equity-focused approach to philanthropy. Unfortunately, individual stories, even well-told and amplified, can be co-opted and reinterpreted outside of the meaning and framework of the people who actually shared the stories.

Data can be an important part of larger processes – network building, resource allocation, policy implication, narrative shifting – but it is subject to the same power dynamics that are in those processes. As we embrace datamaking and take on a more active role in this work, examining our own assumptions about these myths helps us to be prepared to work within or around any challenging power dynamics.

Let’s Get Dialectic in Datamaking

Traditionally, data work has focused on pulling social happenings apart into smaller components to try to understand which philanthropic investments and specific grants might prompt the most social change.

Past approaches, and current time pressures, responsibilities, and siloes make it easy to lose sight of the notion that change is not just about understanding parts but is very much about seeing the big picture. Change, of course, is only possible when we embrace both parts and whole—the notion of dialectic.

After working with many groups focused on improving strategy, and witnessing and facilitating knowledge building, I have come to believe that it is in the conversations where we move from part to whole, as we try to connect the two, that energizes creativity and change. Successful datamaking helps us put equity and dialectics into practice.

To learn more about knowledge building and its impact on equity in grantmaking, check out the webinar, Alchemy in Action: The Dance of Knowledge Building, Grant Strategy, and Equity.