Key facts, figures, and trends among U.S. labor unions

Last week, in honor of Labor Day, we shared an introduction to unions, including six things people might not know about the role of unions in the social sector. In this second blog in a two-part series, we share key facts and figures about U.S. labor unions based on Candid’s data and discuss trends and opportunities for future research.

Unions by the numbers

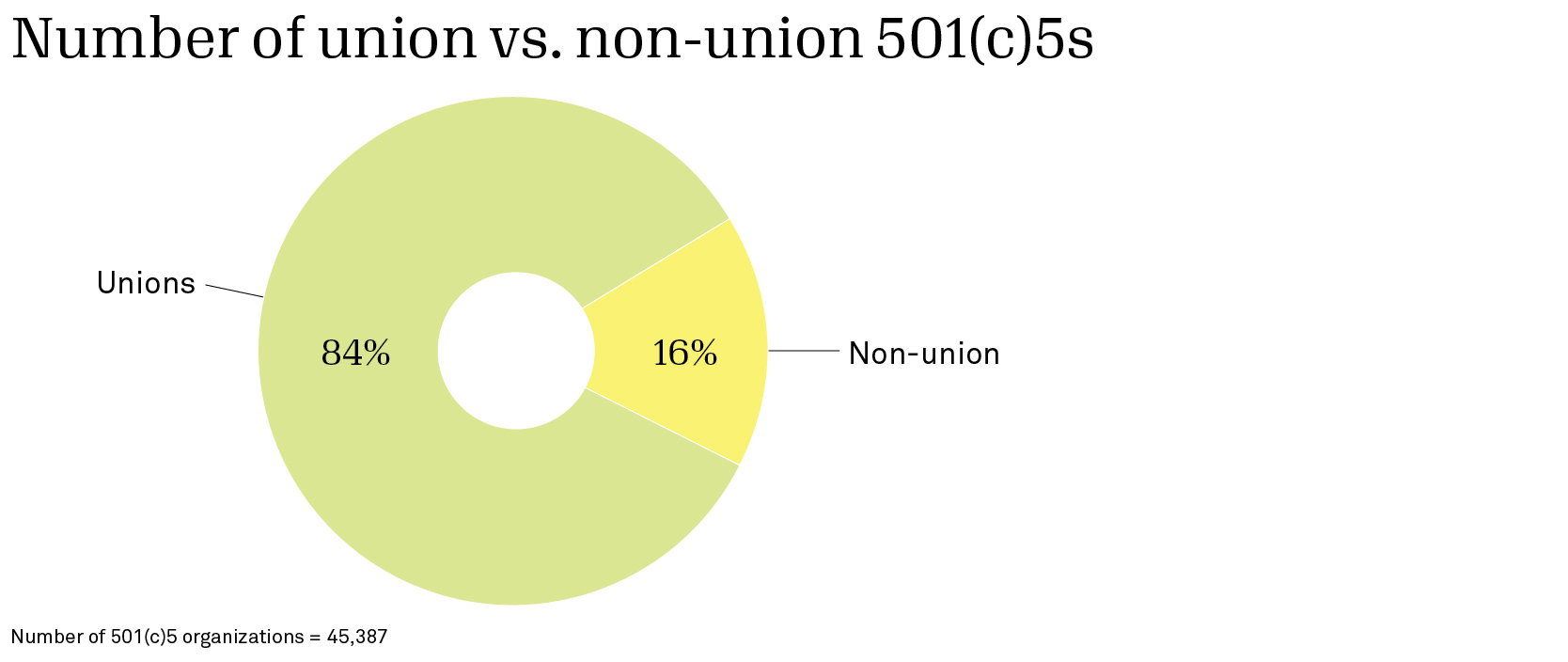

Labor unions fall under the category of 501(c)(5) within the U.S. tax code. The IRS recognizes 45,387 501(c)(5) entities, which include both unions and agriculture/horticultural organizations. Candid reviewed these organizations and found that 38,049 organizations—or 84% of 501(c)(5)s—are unions.[1]

Location

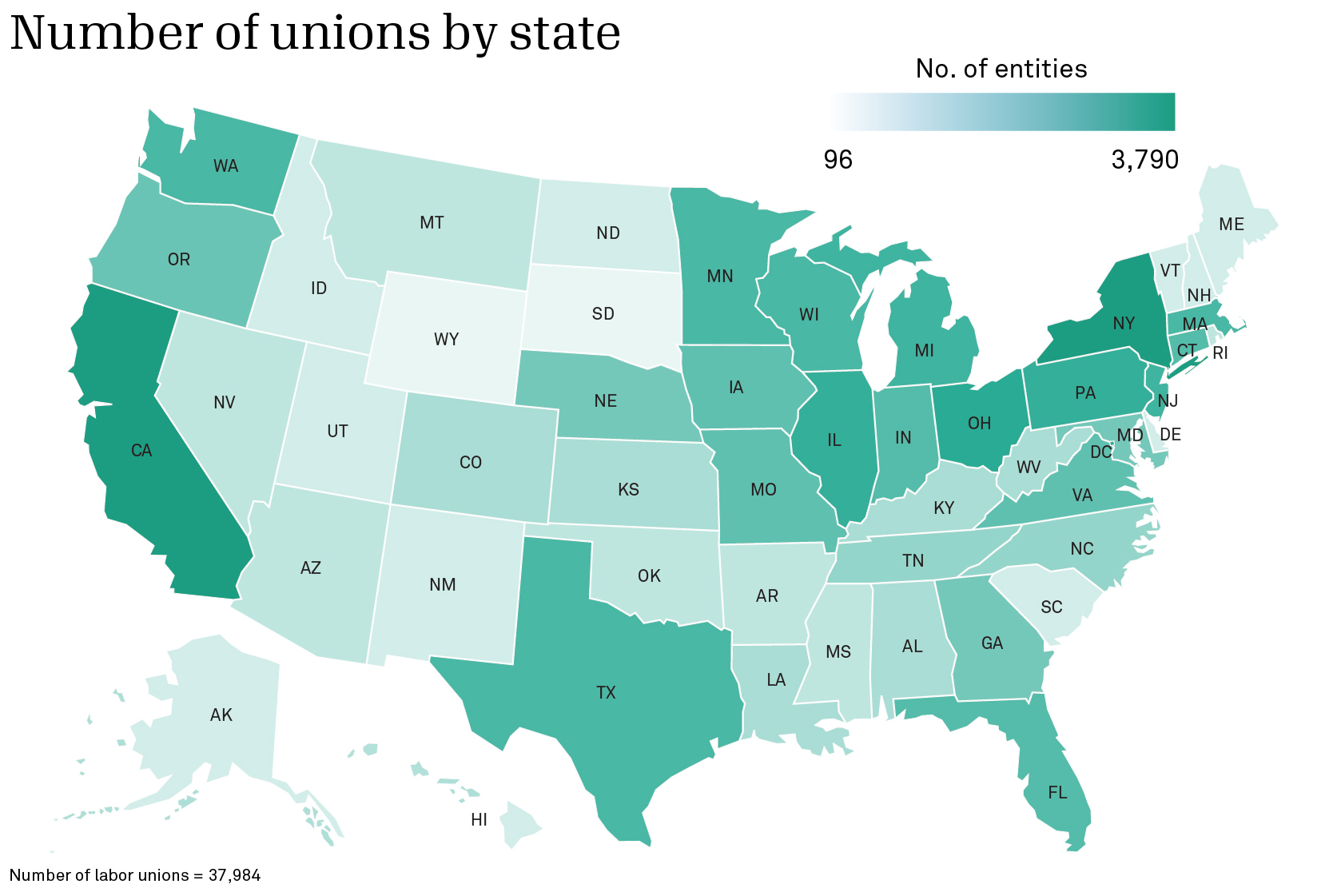

California and New York have the most unions in the dataset, with 3,790 and 3,777 organizations respectively. This is not surprising given that these states also have some of the largest workforces and highest labor union densities, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Financial data

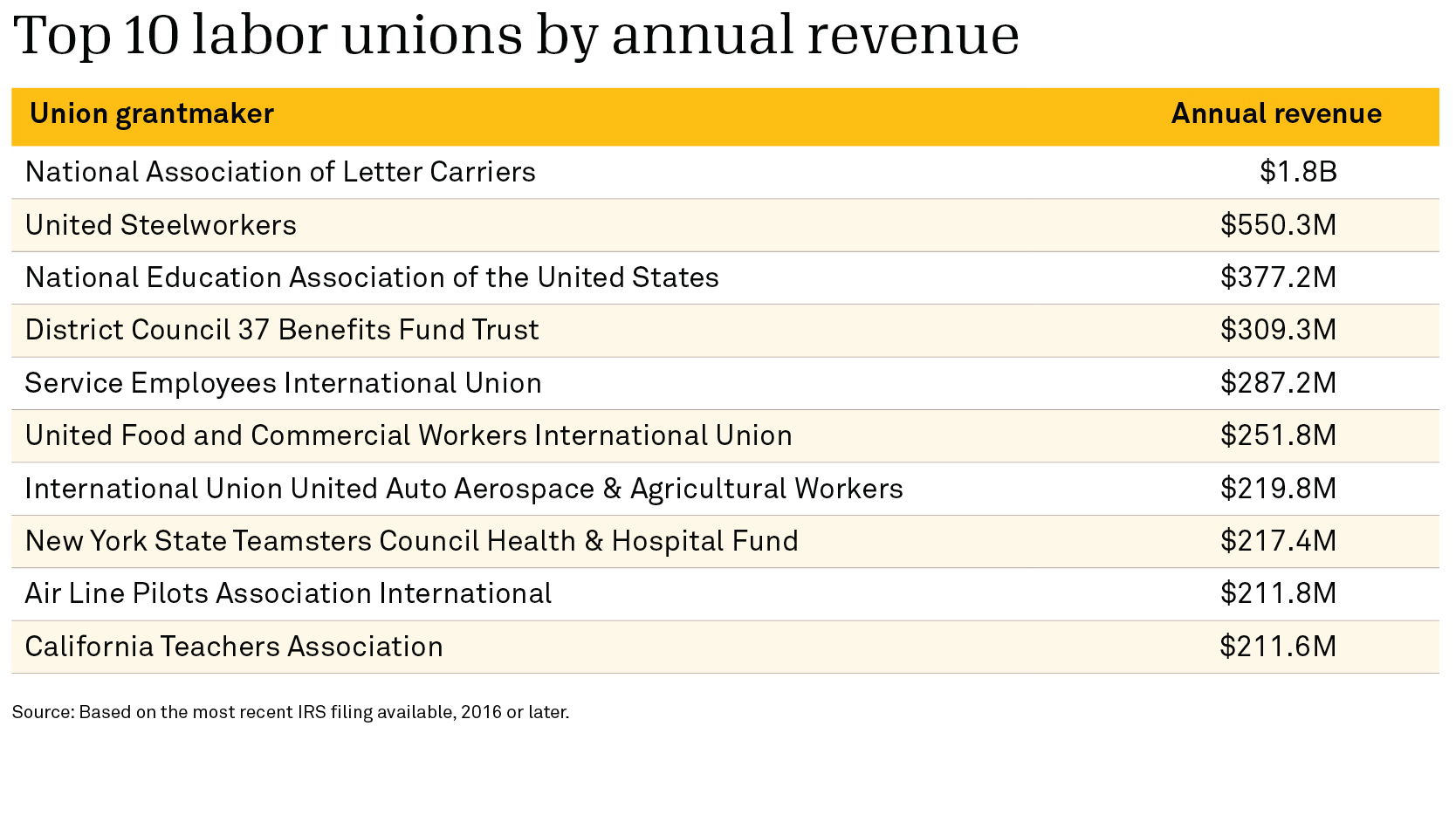

Unions can vary dramatically in size (partially due to the local vs. national structure we explained last week). Most unions are fairly small, and detailed financial information is often not available for these organizations. But based on the 14,901 organizations for which we have financial data from 2016 or later, this subset of unions have $43.1 billion in assets, $26.3 billion in revenue, and $23.7 billion in expenses. In other words, unions as a whole play a significant financial role in the social sector.

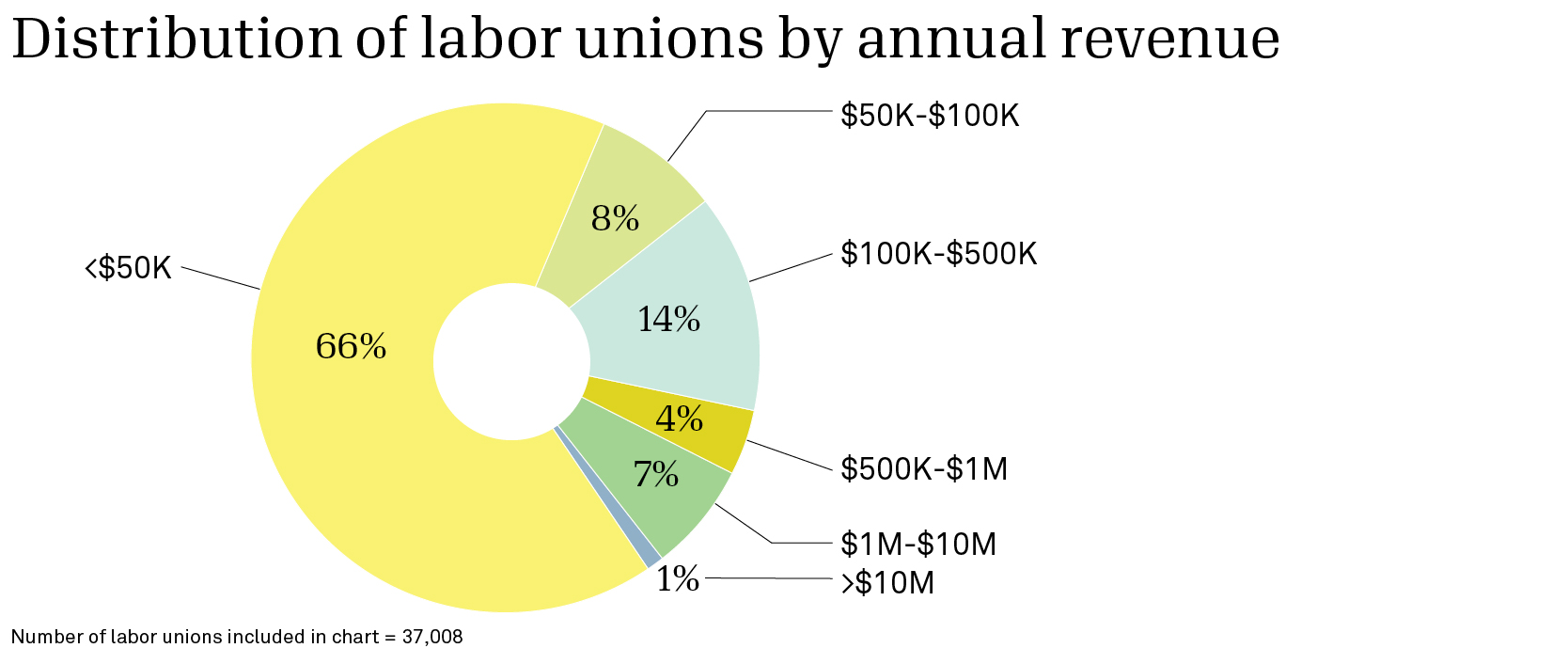

Nearly two-thirds of labor unions have $50,000 or less in annual revenue.[2] Twelve percent have annual revenue of more than $500,000. The national arm of the National Association of Letter Carriers (as opposed to any of the locals) is by far the largest union in terms of revenue, bringing in $1.78 billion dollars. The national arm of the United Steelworkers is the second largest, with a revenue of about half a billion dollars.

Unions, charity and voluntarism

Unions, charity and voluntarism

While this blog is largely focused on new developments in unions’ engagement with philanthropy, it is important to acknowledge that unions have long encouraged their members to be engaged in the community. A study conducted by Roland Zullo and published in the Industrial and Labor Relations (ILR) Review (2011) [3] found that charitable donations to United Ways increased in localities with higher union density and in areas where unions were financially stronger. Further, the study found that union members were more likely to volunteer for charity and to be more engaged in the community in less formal ways (such as going to meetings, tutoring, and mentoring). According to Zullo, the likeliest explanation for this correlation is the way unions have embedded themselves in local charitable networks. Unions often negotiate with employers to allow convenient contributions to charity (most notably United Way) through direct payroll deductions and can mobilize members to volunteer for local nonprofits. Another study published in 2016 found that in cases where workplaces are unionized but workers are not required to join the union (so-called open shops), workers that join the union are likely to be more charitable than workers who do not.[4]

Trends in unions’ engagement with philanthropy

Unions are primarily known for advocating for workers’ rights within specific organizations. However, as union density has declined over the last 40 years, much of the labor movement has taken to engaging more widely with the rest of the social sector. This engagement has created new initiatives that have the potential to transform both unions and the wider social sector. Unions bring their connections to working people, their wide membership base, and their organizing expertise, while newer social justice-oriented nonprofits bring new innovative ideas and connections to populations not included in the traditional labor movement.

One such initiative is the Labor Innovations for the 21st Century (LIFT) Fund. The LIFT Fund was established as a partnership between the American Federation of Labor & Congress of Industrial Orgs (AFL-CIO) and various philanthropic institutions, including the Ford Foundation, Open Society Foundations, and W.K. Kellogg Foundation, with the goal of supporting new forms of worker organizing and producing research to support it. Its purpose is to create partnerships between local unions and workers’ rights nonprofits like the Restaurant Opportunities Centers (ROC) and Worker’s Center for Racial Justice (WCRJ). ROC, WCRJ, and other workers’ centers represent a new front in the labor movement. Rather than being organized as 501(c)(5)s, workers’ centers are generally organized as 501(c)(3) organizations. As organizing certain categories of workers has become increasingly difficult, workers’ centers have focused on delivering services to low-wage (often immigrant) workers, releasing research on conditions in low-wage sectors for advocacy purposes, and developing leadership in workplaces in lieu of actual union representation.

Other unions have taken a more direct strategy of engaging with social movements by incorporating community demands into their collective bargaining negotiations. This strategy, known as “bargaining for the common good,” was a central part of the Chicago Teachers Union’s (CTU) approach during their 2012 strike. In that campaign, the CTU pursued demands beyond their own wages and benefits to aid their students, including: smaller class sizes, a nurse and counselor in every school, and resources for homeless students. While the “bargaining for the common good” approach comes from the grassroots of labor and social justice movements, and the LIFT Fund comes from the top, both demonstrate that unions can and should do more than represent just their immediate members. This approach recognizes that to move forward into the future, unions need to be engaged with wider community stakeholders.

A Provocation for further discussion and research

These blogs provide a starting point for researchers and practitioners to further explore the role of unions in the social sector. We particularly hope to see research conducted on cross pollination of ideas between unions and community nonprofits to explore how ideas or training that originate in either unions or community nonprofits affect the other organization type through staff flows, common networks, and formal engagement. Additionally, unions should be part of discussions around diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) issues given that union membership is extremely diverse, with Black workers over-represented among their ranks. Lastly, we hope to see further exploration of the important role workers’ centers play in creating more labor-oriented social justice. Projects like these are vital for understanding how unions and worker advocacy in general fit into the larger social sector mosaic.

[1] Source: Based on 501(c)(5) organizations appearing on the April 2021 Business Master File. To identify unions, we conducted a systematic analysis of the top 50 NTEE codes by number of organizations and total revenue size (which together accounted for 96.6% of 501(c)(5) organizations and for 99% of the revenue in the dataset), eliminating the codes mostly associated with agricultural and horticultural organizations. We also manually eliminated incorrectly coded agricultural and horticultural organizations via key term searches and by manually going through organizations with large assets and revenue sizes.

[2] Source: Based on the most recent IRS filing available, i.e., 2016 or later. Organizations for which recent filing data is not available but that are required by the IRS to file a 990-N (indicating that their revenue is $50,000 or less) are classified in the under $50,000 category.

[3] Zullo, Roland. “Labor Unions and Charity.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 64, no. 4 (2011): 699-711. Accessed July 19, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41343680.

[4] Booth, Jonathan E., Daniela Lup, and Mark Williams. “Union Membership and Charitable Giving in the United States.” ILR Review 70, no. 4 (August 2017): 835–864. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916677595.